What Do We Know about Donbas?

30.04.2017

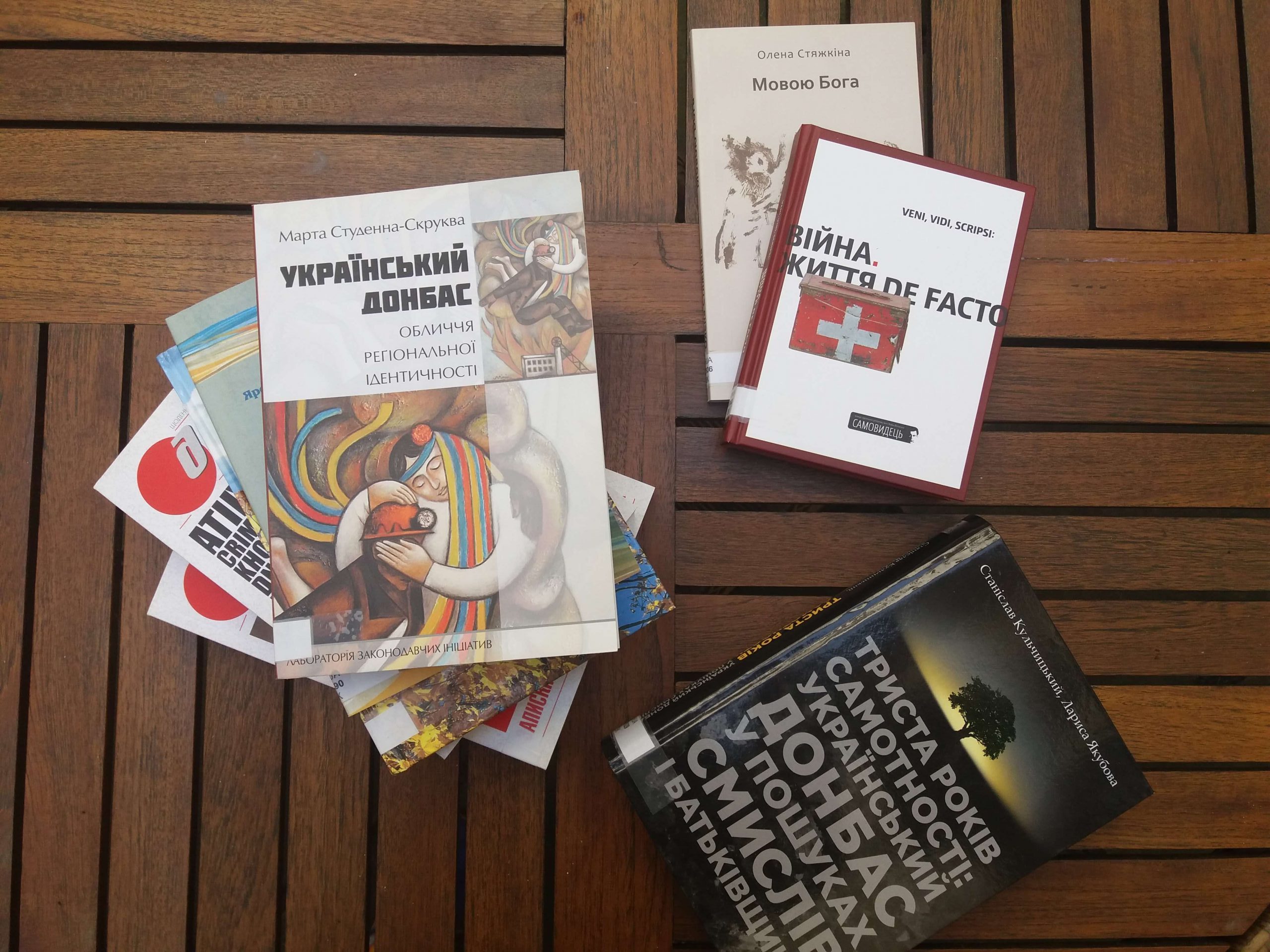

How is the undergoing war perceived today? How do the present day events influence our vision of the history of Donbass? How do historians write in the war and during the war? It is a brief overview of the academic books and essays of the recent years on the history of Donbass, and thus on the current war.

A thick volume by Stanislaw Kulczycki and Larysa Jakubowa "Three Hundred Years of Solitude: Ukrainian Donbass in Search for Senses and the Homeland" (Klio, 2016) is a comprehensive synthesis of the history of Donbass from the times of colonization until present days. While the description of the imperial period authors rather address the concept of modernization, the Soviet times are described primarily as a period of repressions, famine, and "ethnocultural degradation." The story seems to steadily head for one goal – the current war with the separatist republics: "the "Donbas split" is a naturally determined stage of the previous development of Ukrainian statehood and inconsistency of actions of their political establishment that had never realized the completeness of threats and had never felt any responsibility to the society." At the same time, the history of Donbass appears as certain deviation that should be directed to the right way of development because it is an age-old Ukrainian land. However, the unchanged rhetorical figure of the text is the thesis about advance in the areas of "social economic basis" and "cultural achievements" gained counter to collisions of tough fate.

A small book by Yaroslava Vermenych "Donbas as a Borderland: Territorial Dimension" (NASU, 2015) pursues the line to support uniqueness (and often, "deviation") of Donbass, as well as the predicted patterns of war. The notion of borderlands herein does not imply comparative study. Donbass is described as a very special region suffering from the disease of "kitchen-sink cultural and psychological narcissism down to chauvinism signs," excess vulnerability to acknowledging their own merits, the feeling of insufficient protection, social anomy, conflictogenic capacity, etc. It produces an impression that it is better for the society to have a clearly defined and monolith identity. Along with the notion of identity, there are also the notions of mentality and archetypes.

The book by Marta Studenna-Skrukva was written before the war and published in Ukraine in 2014 by the Laboratory of Legislative Initiatives. Conversely, it avoids the projection of the present days upon the historical processes in the past, and does not use the notion of "predicted patterns of history." This work does not emphasize the problems of fitting industrial identity of Donbass within a narrow ethnic and peasant concept of Ukrainian nation. However, it also accentuates that the separatist movement before 2014 was very weak, while the use of regional divisions in electoral games was rather a strategy of local business elites to exert pressure upon Kyiv, rather than expression of serious intentions for separation. The author uses the notion of mining culture and industrial region to show that in reality the Donbass region is not so unique in itself, while similar problems have already been experienced in other countries.

Numerous collections of essays, reminiscences, and coverages on the war in Donbass published recently are also different from each other. For instance, the collection of materials of the "Den" newspaper compiled by Maria Semenchenko "Catastrophe and Triumph. Stories of Ukrainian Heroes" (2015) focuses on heroic deeds, on will and bravery. It is guided by a creed "War is always painful, scary and hideous. But there is always room for good stories and optimism. And also – for Memory." Another collection of the "Den" "I Am an Eyewitness. Notes From the Occupied Luhansk" (2015) includes diary entries and articles by Valentyn Torba, with excerpts from Facebook posts and articles by different authors covering in detail almost the entire first year of the war. The book includes an epigraph from Shevchenko’s poem and presents an opinion of a Ukrainian patriot under occupation.

A book of fiction based on real life personal experience "In God’s Language" (Dukh i Litera, 2016) by a writer and historian Olena Stiazhkina is also dedicated to the events on the occupied territory. At the same time, it presents many more different opinions and shows the complicated interlaced lives of friends, neighbours, and enemies who found themselves on different sides of the barricades in the conflict. Personal and private things are inseparable from collective and public aspects, when friends can easily become foes and vice versa…

The stories by Olena Stepova "All Will Be Ukraine!" also come from the occupied area (2014). The Russian language and Surzhik, the reality of a small town of Chervonopartyzansk in the near-front zone, the everyday life stories of common people create an ironic position on the propaganda media clichés. Despite the irony, the author still emphasizes her position, as well as the idea of the entire book – to evoke readers’ empathy towards Donbassians, to avoid the entirely negativist and scandalous discourse about the region, to find opportunities for a smile in hard times.

One of the most interesting essayist attempts to comprehend the undergoing war is presented in the collection "War. Life de facto" (Tempora, 2016). The essays were the Mike Johansen contest winners for artistic coverage, written not only by journalists but also by soldiers. They present a critical and sometimes pungent analysis of war and its media representation. The authors mostly tend to record the everyday reality avoiding the indubitable heroization or dramatic epicism. The essays provide the degrading descriptions of problems with procurement in the army, the disorganization and bad planning of operations, psychological deformation resulting from battles. Moreover, they prove the immense difference between the experienced reality and the ceremonial reports on the victorious battles avoided in discussions. The protagonists of essays include both soldiers and civilians, refugees, mothers of the fallen looking for bodies of their children. A historian and a soldier Oleksandr Koba is one of the most interesting authors in the collection. In his autobiographic essay, he gives a vibrant description of emotions of a soldier with the posttraumatic syndrome but still concludes the following:

"Soldiers and people who experienced hell will never romanticize the bloodshed. The same as no lasting myths can be created out of a mere boredom. That is why only those would benefit who had never seen the war but make large profits off it. You come to think that war turned into a sort of weird relic of humanity, the utmost nonsense. The bullets and shells seem to never be able to stop the war. It can only be stopped by the schools teaching kids to think critically and respect each other."

Credits

Сover Image: Center for Urban History