The past, present, and prospects of American workers' history

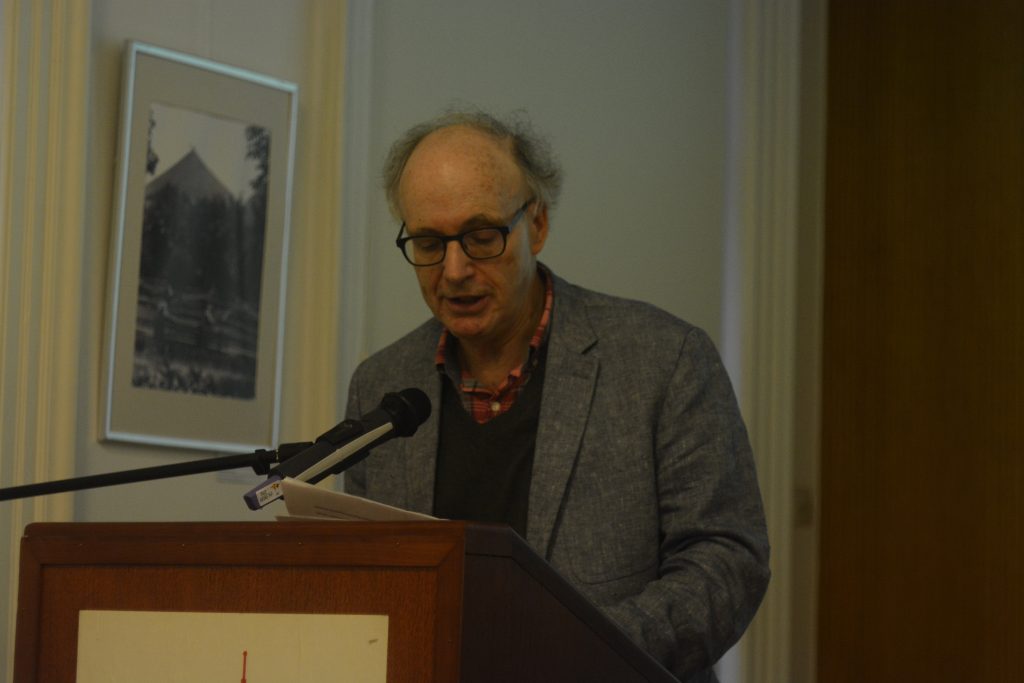

Daniel J. Walkowitz

New York University25.6.2015

Center for Urban History, Lviv

Labor History in the United States underwent a profound shift in the 1960s and 70s, changing from the study of trade unions to the study of the working class. The shift occurred in response to several changes. First, universities, formerly limited to elites, democratized with entry of World War Two veterans and second and third generation children of immigrants from the growing ranks of the middle class. Second, igniting a decade of protest that often resulted in violence, African Americans began to demand equal rights. They had fought in the World War and racism continued to deny them their share of the postwar prosperity. In the 60s, they found themselves fodder in the U.S. military engagements in Vietnam. The scholarly manifestation of the social and cultural movements of the 1960s was a New Social History that insisted that the stories of working people, African Americans and women -- all the new students in the Universities -- mattered. And rather than a story of Labor told by labor leaders, it would become a history "from below" of the working class.

The next decades would see this history blossom, but its ascendency in a new conservatism of the era of Reagan-Thatcherism soon received resistance. Some under the rubric of cultural history complained that local in depth cases were balkanizing the past and they urged for a grand narrative. Pressing to reassert the older stories, they insisted powerful white men still needed to be at the center of the story. By 1990, feminist labor historians influenced by post structuralism and "the linguistic turn", and in the last decade, an emerging field of "capitalism studies" offer fresh, exciting new transnational perspectives on work, class and subjectivity.

Today, deindustrialization has eliminated many manufacturing jobs, placing new challenges and opportunities on the labor movement on the one hand, but creating vast new inequalities and dependence on precarious labor on the other hand. Neoliberal state attacks on labor coincide with an ideology that elevates consumption over class identities, asking how do we organize a working class that often identifies as middle class, and in the global economy, what lessons are there in this history for labor in the U.S. and elsewhere? This lecture engaged these issues through a recounting of the changing ways labor historians have written the history of work and labor in America.

Daniel J. Walkowitz

holds joint appointments as professor in the Department of History and department of Social and Cultural Analysis at New York University. A labor and urban historian who for nearly two decades directed the Metropolitan Studies Program at the University and pioneered its Public History Program. He is presently writing a book on the politics of Jewish heritage tourism in eleven cities and eight countries, including Lviv and Kiev in Ukraine.

Credits

Сover Image: Soda Head