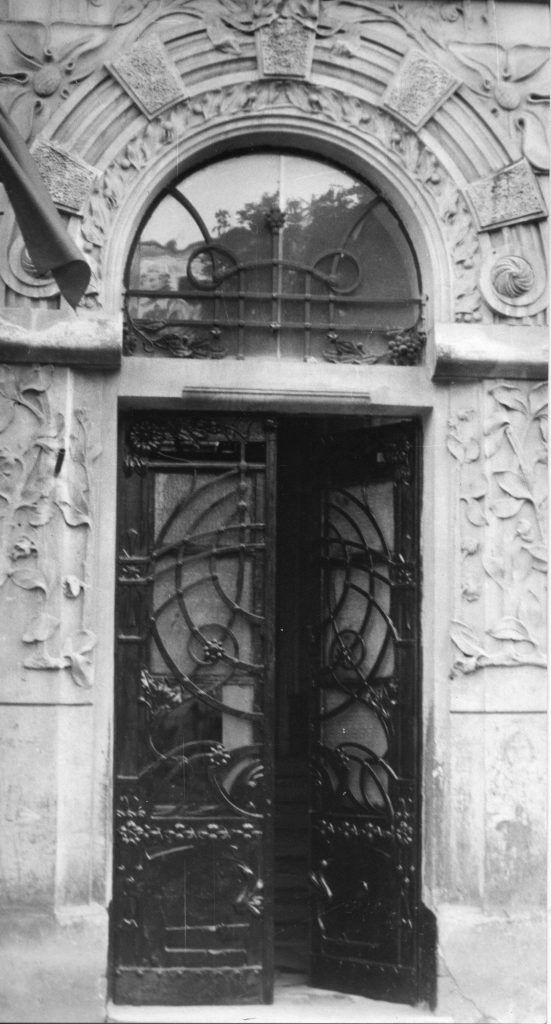

In October 2006, the Center for Urban History inaugurated its newly renovated premises at 6 Bohomoltsia Street. Conceived by Lviv’s most renowned Art Nouveau architect, Ivan Levynskyi (Jan Lewiński), and located in one of the city’s most remarkable secessionist streets, the building itself proved to be a symbol of the Center's identity and presence in the city. It also came to serve as a model for renovation projects that combine modern interior design with the sensitive handling of historical substance. The project’s successful implementation was the result of fruitful cooperation between Austria (Herbert Pasterk as project leader) and Ukraine (Mykola Prokopovych as a local partner architect) and companies.

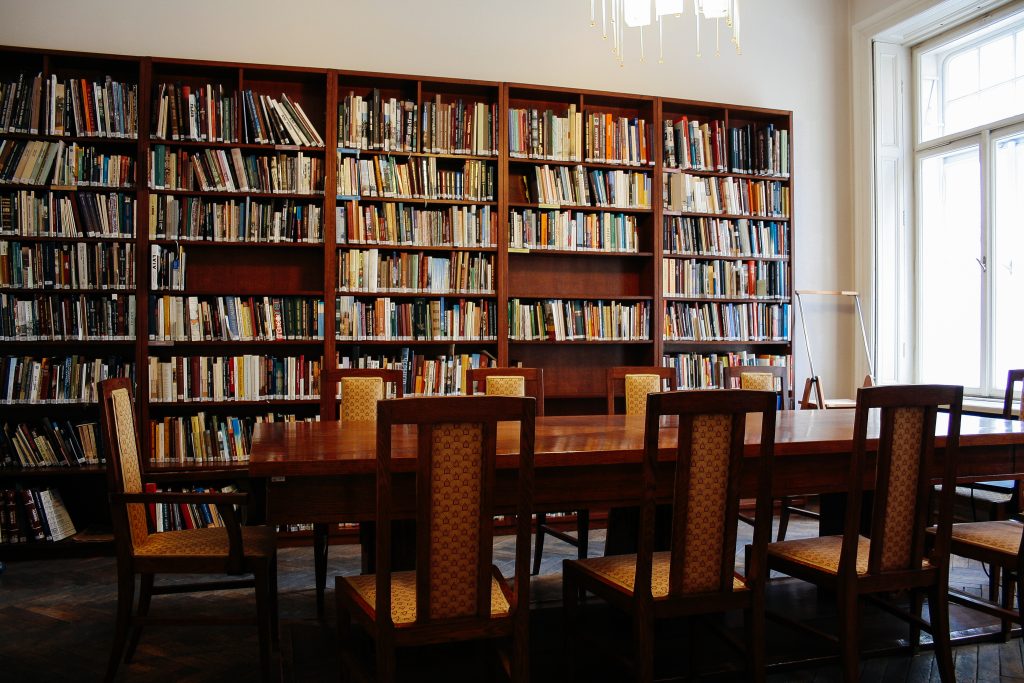

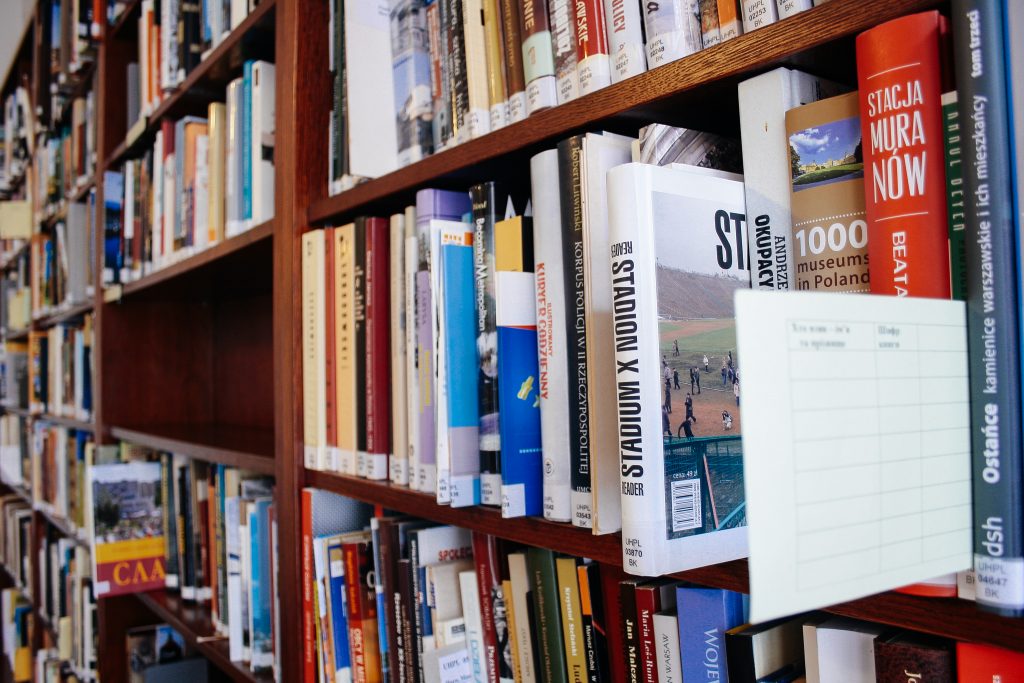

In the course of time, the core parts of the building (a reception area, library and office space) were expanded to include a conference room, an exhibition space, guest rooms, and most recently, a cafe. The spatial layout of the Center’s premises reflects both the diversity of the working spaces from research to public history, as well as the different stages of the Center’s development: from three rooms in 2006 to three levels today.

As "6 Bohomoltsia" is an integral part of our identity, we investigated the building’s architectural history, the life stories of its inhabitants, and the multifaceted past of its immediate neighborhood. Bohomoltsia Street is illustrative of the history of the city in the 20th century. The small street was laid out and built 1904-1908 and was originally named for the well-known Polish poet Adam Asnyk. Its creation came at a time when Lviv was implementing new ideas in city planning, architecture, and neighborhood development. The street soon became synonymous with comfortable living in an urban environment and was popular with the middle class and with urban professionals, including doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, photographers, architects, engineers, government officials, and university lecturers. Some of these residents also maintained offices, bureaus, and tailor shops on the street. Some examples of residents in the first half of the 20th century were Adolf Beck, a professor of medicine and the rector of the Lviv University in 1912-13, Yevhen Olesnytskyi, a lawyer and politician, and Stanislav Progulskyi, another doctor and university professor. The Second World War, the Holocaust, and post-war deportations tragically impacted the residents of the street, forever changing the human component of the block while largely leaving the buildings intact: Stanislav Progulskyi and his son Andrzei were shot dead by the Gestapo in August 1941 at Vulky Hills in Lviv; Adolf Beck committed suicide in 1942 during the forced relocation of Lviv's Jewish community to the ghetto. Following the war, most of the remaining pre-war residents of Adam Asnyk Street were forcibly relocated to new Communist Poland, and new residents were settled on the renamed Akademik Bohomolets Street in Soviet Lviv.

Focusing research on a single street like this allowed us to tell its story from different viewpoints and in different formats, such as a collection of oral history interviews, a separate research topic within the digital project Lviv Interactive, and an exhibition in 2010. To conclude this exhibition on Bohomoltsia Street, the Center staged a Street Festival on the square facing the building and unveiled a plaque describing the history of the street and its architect, Ivan (Jan) Levynskyi. Combining on the one hand research in urban planning, micro-historical focus, oral history, and digital tools, and on the other hand, public engagements in a contemporary neighborhood reflects the Center’s credo of being a civically engaged academic institution reaching out to the urban public. This combination makes 6 Bohomoltsia an inclusive and welcoming space for conversations, meetings, and sharing different viewpoints.